Today we were truly following in the wake of the Viking explorers and quite possibly of Irish monks also. Vikings for sure: for it was across this strait in 982AD that Eirik the Red, banished from Iceland following a conviction for manslaughter, sailed westward to discover a new land. His landing today is commemorated at Eiriksfjord at what is known as the Eastern Settlement. A generation later, as the millennium turned, his son Leif Eriksson crossed the same strait to bring Christianity to Greenland, an epoch-marking event commemorated by the small church that has been re-created at Brattahlid.

Although the cold Greenland Current keeps eastern Greenland icebound for much of the year, the southern and western shores are warmed by the lingering effects of the North Atlantic drift making them accessible to navigators following the stepping-stone route from Ireland, Britain and Norway via the Faroes, Iceland, Greenland and eventually on to the North American continent, a voyage credited in the Icelandic saga to Leif Eriksson. The latter’s arrival in the New World as the first millennium turned marked a significant moment in human history: following mankind’s first wanderings out of Africa those that had migrated eastward now met the descendants of those who were traveling westward, an encounter that seems not to have been a cordial one since the next such encounter was postponed for five hundred years.

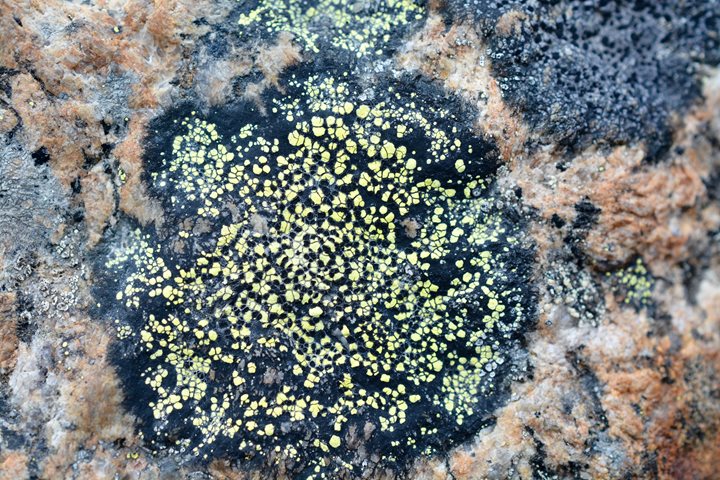

That the Vikings landed in the New World is not in doubt; L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland is an accredited archaeological site. As far as the Irish monks are concerned, our Global Perspectives Guest Speaker on this voyage, Tim Severin, demonstrated back in 1976 that a small party of Irish monks in a sea-going currach could have made the same journey following the same “stepping stone” route. We were treated to a splendid presentation from Tim Severin in the morning with a chance to view newly re-discovered film footage taken during the voyage. Those Irish monks were following an eremitical tradition that had its roots in the Arabian Desert. Like the Desert Fathers, they sought the solitude of deserted places and were willing to cast themselves adrift on the ocean as an act of faith. Their voyage was an exercise of faith, not a voyage of exploration by monks whose lifestyle was characterized by austerity and erudition.

Our own transit of this historic passage was not by wicker craft or oak frame vessel but in an ice-class expedition vessel, the gleaming engine room the object of many compliments during an afternoon tour.